An interview with Mark Pearson, recipient of the 2020 International Award of the Photographic Society of Japan

Mark Pearson is the founder of Tokyo-based gallery and photobook publisher Zen Foto Gallery as well as a co-founder of shashasha. In recognition of his many achievements as a gallerist and publisher and for his ongoing activities in the world of Japanese photography, Mark was recently given the 2020 Internatioanl Award by the Photographic Society of Japan.

On the occasion of this award, we have asked Mark a few questions about Zen Foto Gallery, photobook publishing and his views on the Asian photography world.

Hello Mark, you have just been selected as the recipient for the 2020 Photographic Society of Japan’s International Award. Congratulations! How do you feel?

I feel happy. I feel grateful to the judges. I am glad to share this award with all who have enabled us all to build a community around Zen Foto. I am happy for all of us in the Zen Foto family.

The Photographic Society of Japan provides the following reason for their decision: “After 30 years in Japan, Mark Pearson established ‘Zen Foto Gallery’ with a focus on Asian photography. Adding to the exhibition he organized and the photobooks he published and produced, Mark Pearson is also an active collector of photography. Our decision is in honor of his many achievements.” What meaning does the award hold for you personally?

I appreciate those specific comments. This award reminds me of what we have done in the past decade, and I realise that it is the best thing I have done in my entire life. At times it has been difficult. It has always been a heavy burden financially. But it has brought great joy and satisfaction. I am very lucky to have done it.

Until my interest blossomed in photography and establishing Zen Foto my life was already very blessed. I had a simple but happy childhood, loving parents, lovely sisters. A good education set me on the path to a secure career. I was able to marry quite early and by the age of 30 already had three children.

Now I have just turned 60. If I had done nothing else, I could look back on my life as having been satisfactory, but there would have been nothing out of the ordinary. As the years passed by I increasingly felt that my financial career, while fascinating at times, was ultimately pointless. What good does it do to have engaged in a million financial transactions that have shifted small amounts of money here and there?

Photography has been an outlet for my own creative urges, a source of vicarious pleasure gained from the work of others, a source of inspiration and finally the feeling of community within the Zen Foto family.

Could you tell us what made you focus on photography in Asia (and Japan and China in particular)?

Very simply, I was living in Japan when the urge to explore the world of photography came to me. I started taking photographs, trying to learn more, joined the photography circle at Place M and began my collection. A little later my eldest son Phillip was studying in China and it was visiting him that opened my eyes to that fascinating country and to an involvement with the photography of China.

It is impossible to talk about your achievements without also talking about Zen Foto Gallery’s journey, which is now in its eleventh year. How do you think Zen Foto Gallery is valued in Japan and internationally?

That is for others to say. Despite many years of visiting, living, raising a family and working in Japan, I was an outsider and particularly so in the photography world. Being an outsider closed some doors, but it brought a freedom from certain expectations. We worked with artists who had not had as many opportunities within the established gallery world, with young artists and older artists who did not fit the existing structures.

Because I am British and Amanda Lo is Taiwanese, I knew that we could help to reach the broader world outside Japan. We have tried to bring information in English and Chinese as well as in Japanese and we have distributed our publications globally, especially since establishing shashasha for selling photobooks online.

The large catalogue of published photobooks (140 titles so far) is one of Zen Foto Gallery’s most remarkable achievements. Could you tell us a little about the relationship at Zen Foto between publishing and exhibiting? Also, could you tell us which element of the photobook publishing process you enjoy the most?

At the outset I intended simply to be an exhibition gallery and had no serious thought of publishing. We started making a simple record of the exhibitions. Those simple booklets from 2009 are still on our shelves, in museum libraries and with curators. The prints are less often seen after the exhibitions. The books are the medium through which the photographs reach a wider audience. They have been the catalyst for photographers to be seen by foreign collectors and curators, and this has expended the opportunities for a wider appreciation of their work. As the years have passed by, the books have assumed a greater importance.

Over many years, you have managed to create an invaluable collection that captures the history of Japanese photography. What are your criteria for selecting photography for your collection?

The criteria are simple. Asian photography, centred on Japan and China and photography that speaks to me in some way. This is often subjective and difficult to define but includes work that has a historical or social relevance, aesthetic beauty, or an emotional resonance.

A couple of years ago I saw a superb exhibition of the collection of Sir Elton John, which comprised many stunning photographs, but it seemed to be a collection of unique pieces. In contrast, I like to have a complete series. I can appreciate an unforgettable single image but also the cumulative impression of the work, the place, the people that one obtains by viewing an entire series. When we think of the work of Suda Issei or Kitai Kazuo and their peers, perhaps much Japanese photography works through the accumulation of individual images into a series, and this might makes them more suitable to be collected into book form. My collection follows this tendency. I suppose that this also satisfies the collector’s insatiable, if not fatal, desire for a collection to be complete.

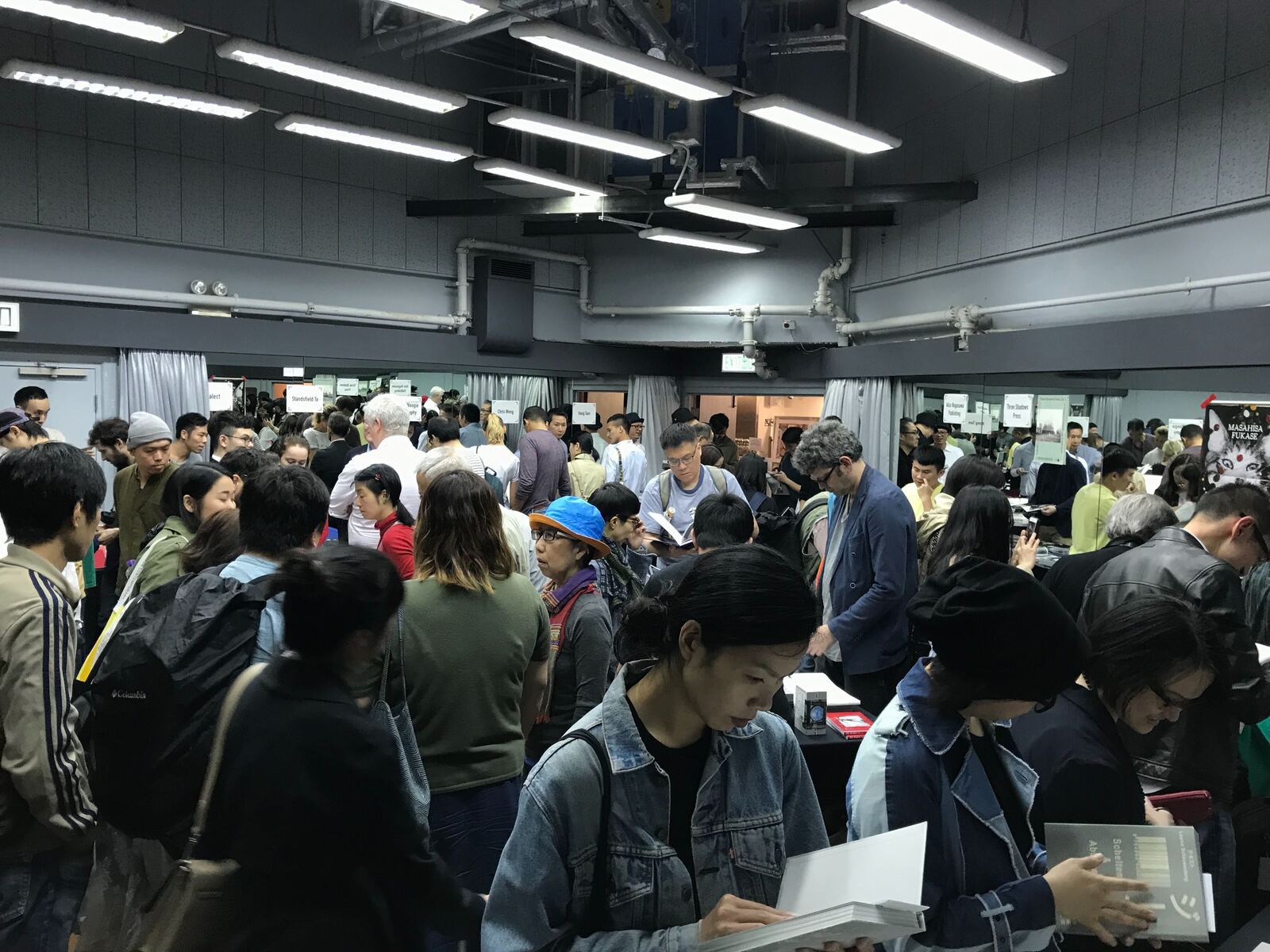

As director of the HK Photobook Fair, which has been held five times so far, you have a unique overview – how do you think the Asian photobook landscape has changed in recent years?

Photobooks are not a good commercial proposition. It is hard to come up with the names of more than a handful of people who have made a living through publishing photograph books. Rather, there are many who have become poor. As the years go by, and people become enveloped in digital worlds, people acquire fewer material goods. We are far from the days of printing runs of tens of thousands for photography magazines and thousands of copies of books. I hear that even the Asahi Camera Magazine is to close. So photobooks increasingly need sponsors of one kind or another. Sadly, I don’t see very many sponsors who are active these days.

We usually print around 500 copies of a book and consider ourselves lucky to sell them over the course of several years. Even this does not cover our costs. A book like Yang Seung-Woo’s “Shinjuku Lost Child” which has just gone into its 4th printing of 500 books is an exceptional one-off success.

Could you share your opinion on current trends in Japanese photography? We would be happy to hear about both positive and negative aspects.

I am not qualified to comment on contemporary Japanese photography. The subject is too broad and I do not get to see most of it. From my limited viewpoint I could make a few tentative observations.

First, there are a large number of very talented and dedicated photographers. But many are somewhat similar to each other. I don’t mean that in a pejorative way. It is simply natural to be interested in certain things and to use techniques and methods that result in similar outcomes.

Second, conceptual photography seems to be rarer in Japan than overseas. When we look at photography shown in international fairs such as Paris Photo, much of what is on display is reliant more on concepts and techniques derived from commercial and fashion photography. It is shiny, bold and explicit. I am not against perfect execution or conceptual work, which can be attractive and interesting.

There is excellent technique of course. Usui Kazuyoshi’s Showa series is a fine example. In Japan, photography is not so much considered decorative, technique is not flaunted but is a means to an end. The photograph is a form of expression, often realistic, personal and introspective, suggesting certain feelings and emotions rather than telling you what to think. A book like “Yokushiroku” by Hirose Kouhei is a good example. Often the technique is superb, but is not flaunted, as we see in Arimoto Shinya with “Tokyo Circulation”.

There is a spectrum of achievement and qualities, but at least I can say that much of the photography that we show and publish tells us something about the human condition. Examples such as Hashimoto Shoko’s “Goze”, Tonomura Hideka’s “They Called Me Yukari”, Chan Wai Kwong’s “Yau Ma Tei”, Nakafuji Takehiko’s “Hokkaido: Sakuan, Matapaan” and Nishimura Tamiko’s “Ryojin” bring us to a deeper understanding of humanity, and of ourselves. It is such reflections on the beauty and sadness of existence that might be said to characterise the kind of photography that appeals to me.

A lot has happened in the past 30 years, from exhibiting at fairs in Japan and overseas to award wins for books you published, holding your own fairs, and sadly the passing of artists close to you. Is there any event or moment in particular that has left a deep impression on you?

When I start to think of the artists we have worked with over the years I simply feel incredibly privileged. They are excellent artists, photographers and people.

Tokyo Rumando’s “Orphée” is one stand-out memory. I saw her exhibition of photographs taken in love hotels and invited her to show with us. That resulted in the book “Rest 3000~ Stay 5000~”. We published a modest little book for her next series “Orphée” which was discovered by Simon Baker at our table in Polycopies Paris in 2014 and led to her participation in an exhibition in Tate Modern in London. It was such a thrill to be part of her breakthrough.

I also think with great affection of the many many meetings we have held over the years. Hosoe Eikoh used to pop in at unexpected moments to see our shows. I took great encouragement from him. Such a passionate and intelligent man.

Suda Issei was another wonderful partner. I was in awe of him. We published several books for him during his lifetime, including the last book published during his lifetime. It seemed fitting that it was his most personal work “The Mechanical Retina on My Fingertips”.

Most lately we had been working on a new book for Kurata Seiji. Kurata-san was a fastidious artist. It was heartbreaking to observe his physical decline in recent years, but still a great shock to learn that he had passed away earlier this year. We hope to honour his memory with the forthcoming book “Eros Lost”.

We have been engaged with several artists right up to the end of their lives, creating books and exhibitions that would not otherwise have come to fruition. It has been sad to lose some peerless photographers but the memories are bittersweet, and that is how it must be.

You also publish your own work in photobooks alongside artists like Chris Shaw, Tokyo Rumando and Chan Wai Kwong. What is it about taking photographs that you find exciting?

The desire to learn to make better photographs led me into the world of fine art photography with Zen Foto and this desire is still with me. Having seen the works of so many photographers over the years has definitely informed my own photography. I always find myself inspired by the last photographer’s works that I have seen.

But ultimately I am yearning to make something of beauty, something that touches my heart and perhaps it can also touch the hearts of others.

― Mark Pearson, 3rd June 2020